BA (Hons) Architecture

Year 3

AD3.1

Architectural Design

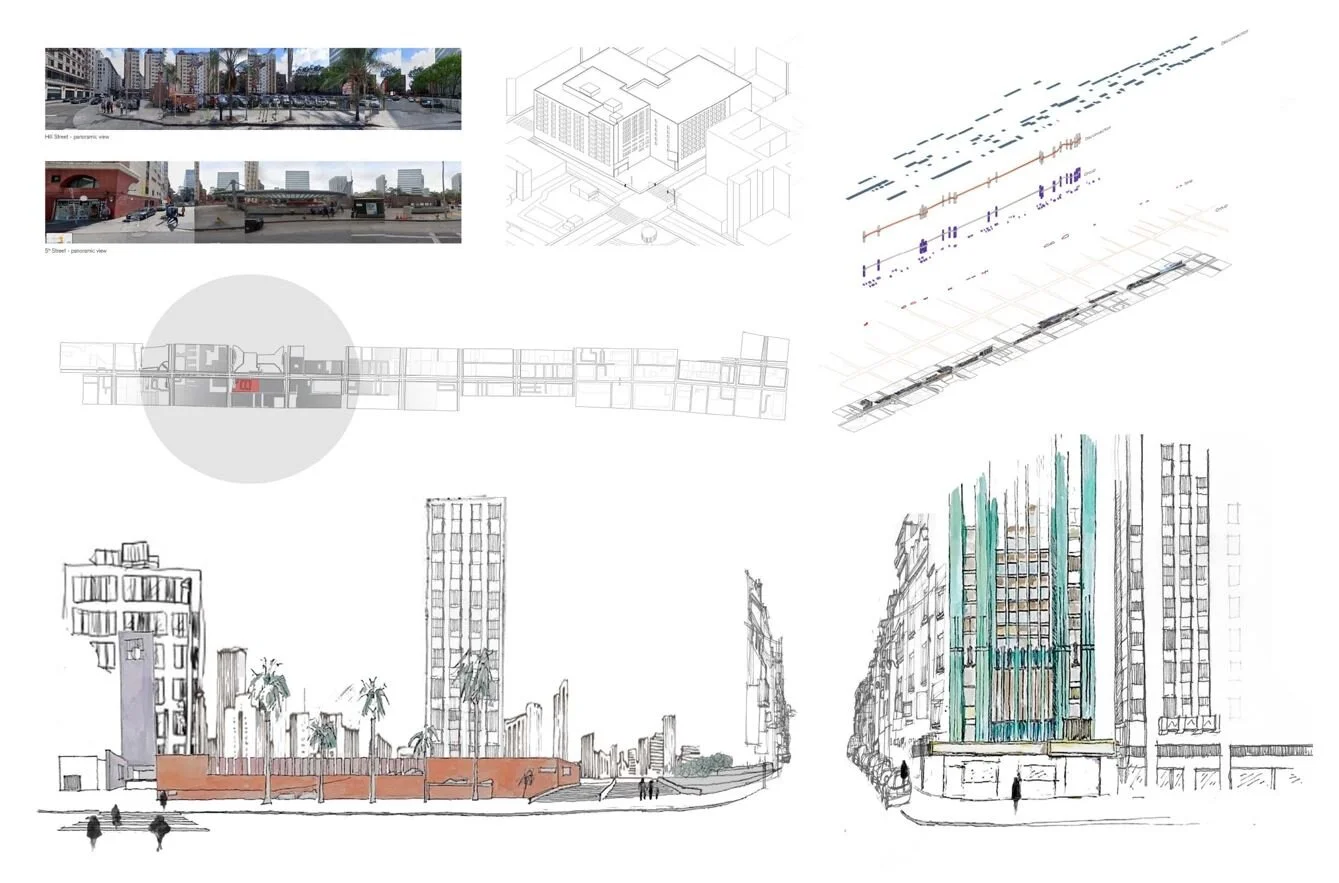

The module forms the first phase of the level 6 design comprehensive design thesis project. The year has a balance of groups covering a diversity of questions and innovative approaches to process, material, sustainability and techniques of fabrication which relate to the research specialities of the school.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.1, GC1.2, GC1.3, GC2.1, GC2.2, GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GC4.1, GC4.2, GC4.3, GC5.1, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.1, GC6.2, GC6.3, GC7.1, GC7.2, GC7.3, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2, GC9.3, GC10.1, GC10.2, GC10.3, GC11.1, GC11.2, GC11.3, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.3, GA1.4, GA1.5, GA1.6

Joe Sedgwick - Discontinuous Genealogies

Maria Rana - Discontinuous Genealogies

Ruby-Mae Brookes - Discontinuous Genealogies

Fin Gilbert - Abstract Machines

Hazel Rutherford - Abstract Machines

Gabriel Tallara - Abstract Machines

Callum Suttle - CityZen Agency

Emilie Andrews - CityZen Agency

Paige Jones - CityZen Agency

Asmaa Ahmed - The Plan

Niamh Condren - The Plan

Sam Pick - The Plan

AD3.2

Architectural Design

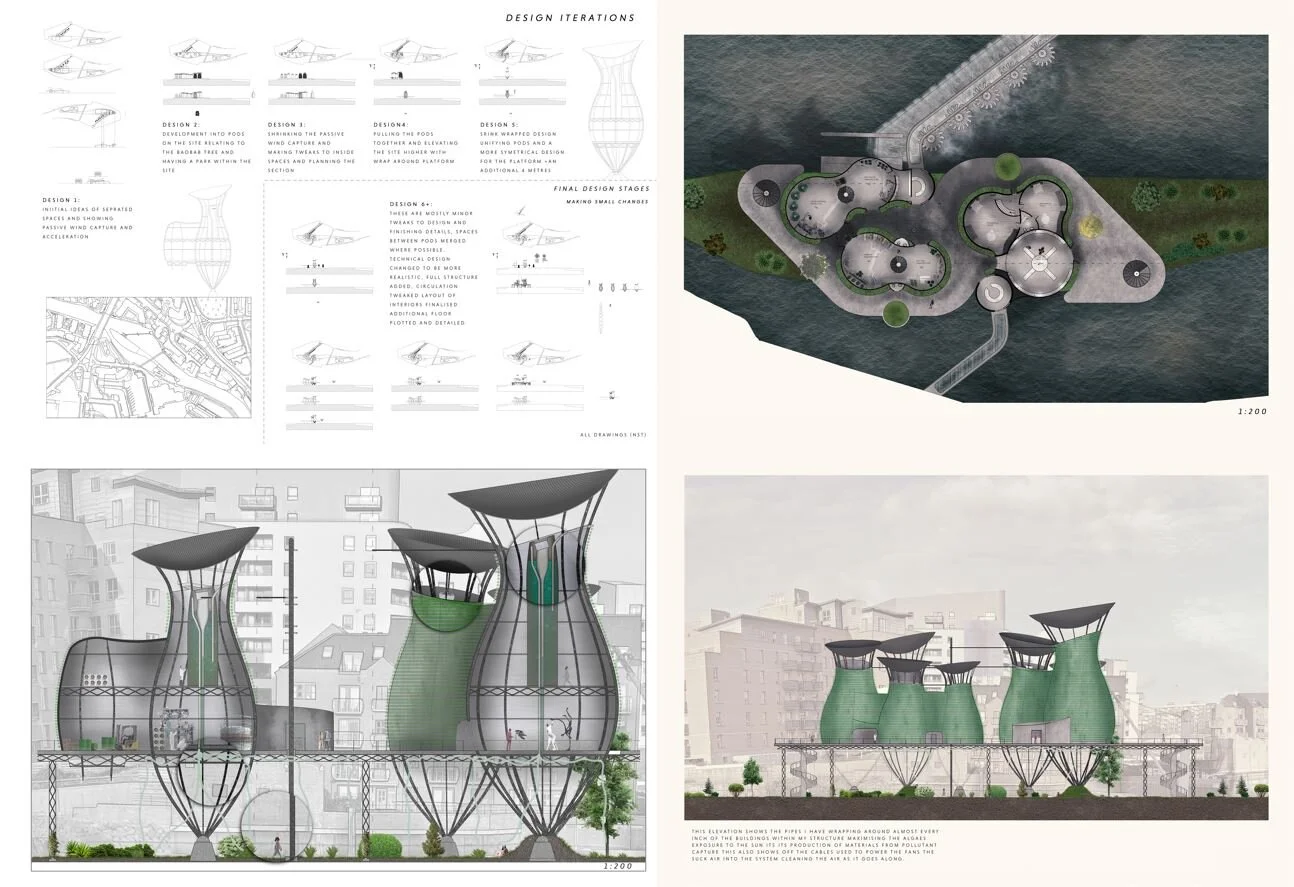

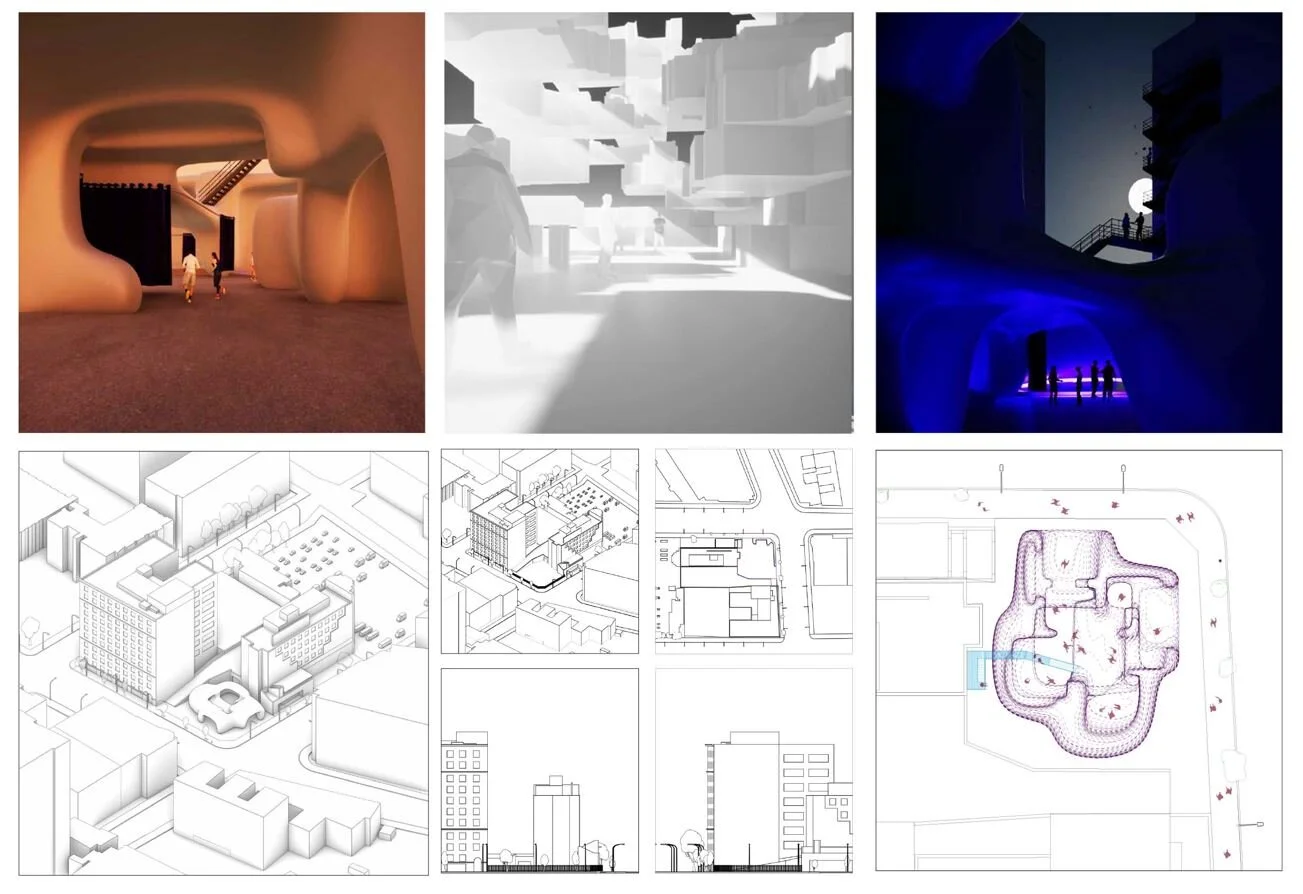

AD3.2 forms the resolution phase of the comprehensive design thesis project. Students are required to present a finished scheme of appropriate scale and complexity demonstrably underpinned by the investigations undertaken in AD3.1. The resulting proposal should establish how strategic ideas translate into physical and material form, both at a strategic and detailed level.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.1, GC1.2, GC1.3, GC2.1, GC2.2, GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GC4.1, GC4.2, GC4.3, GC5.1, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.1, GC6.2, GC6.3, GC7.1, GC7.2, GC7.3, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2, GC9.3, GC10.1, GC10.2, GC10.3, GC11.1, GC11.2, GC11.3, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.3, GA1.4, GA1.5, GA1.6

Eve Walton - Discontinuous Genealogies

Dominic Stewart - Discontinuous Genealogies

William Cox - Discontinuous Genealogies

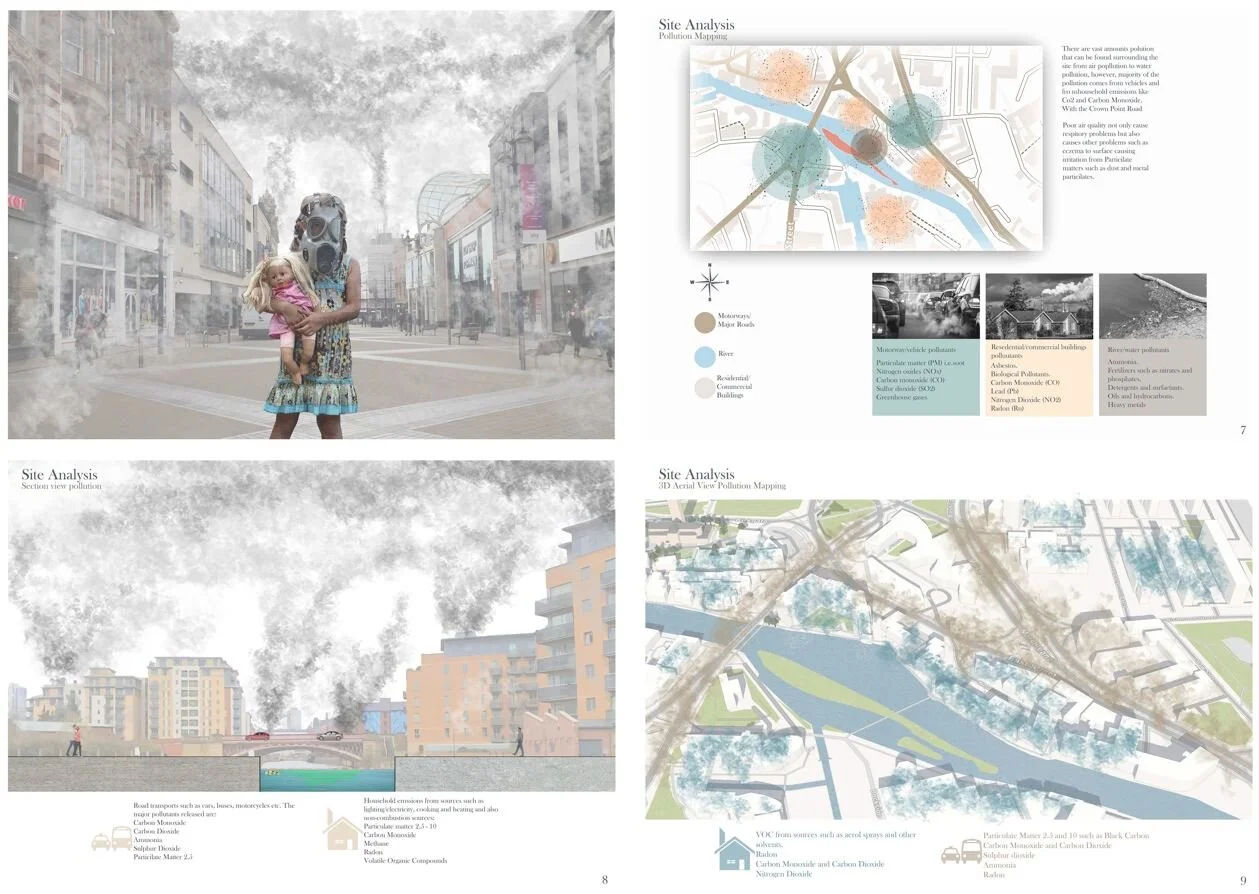

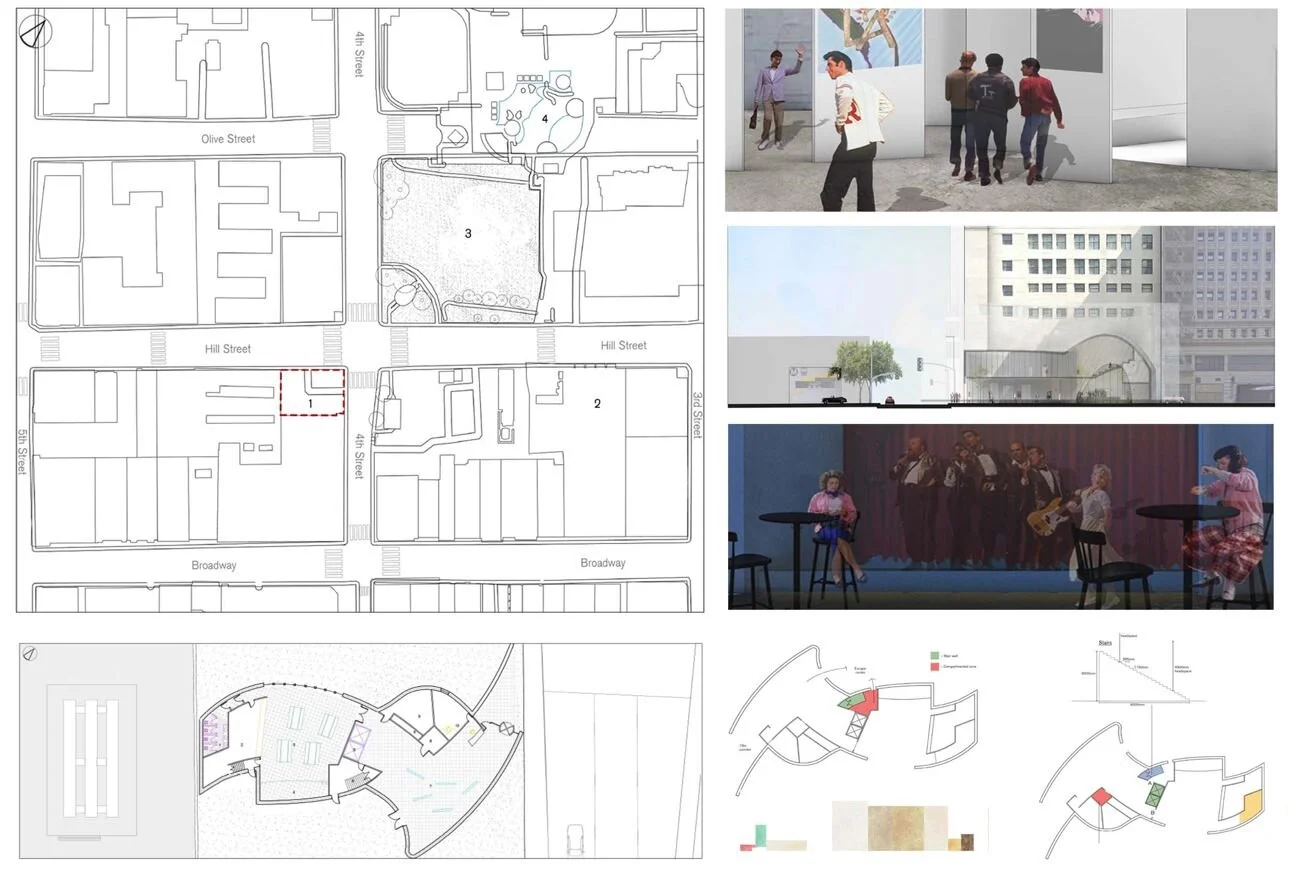

Asmaa Ahmed - The Plan

Sam Pick - The Plan

Tom Brown - The Plan

Joe Clark - Abstract Machines

Cassie Norrish - Abstract Machines

Gabriel Tallara - Abstract Machines

Emilie Andrews - Cityzen Agency

Callum Stuttle - Cityzen Agency

Luke Singleton - Cityzen Agency

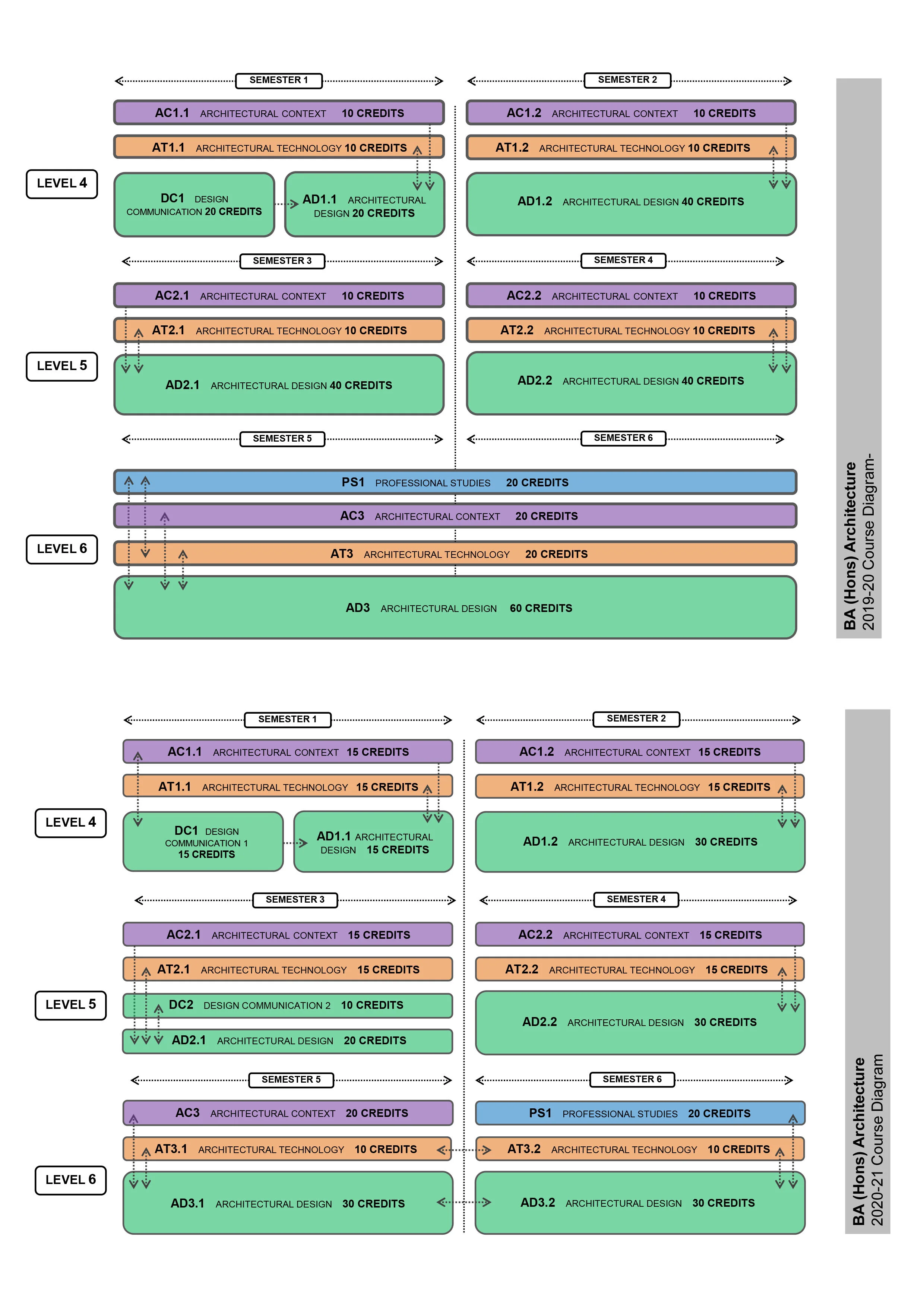

AT3.1

Architectural Technology

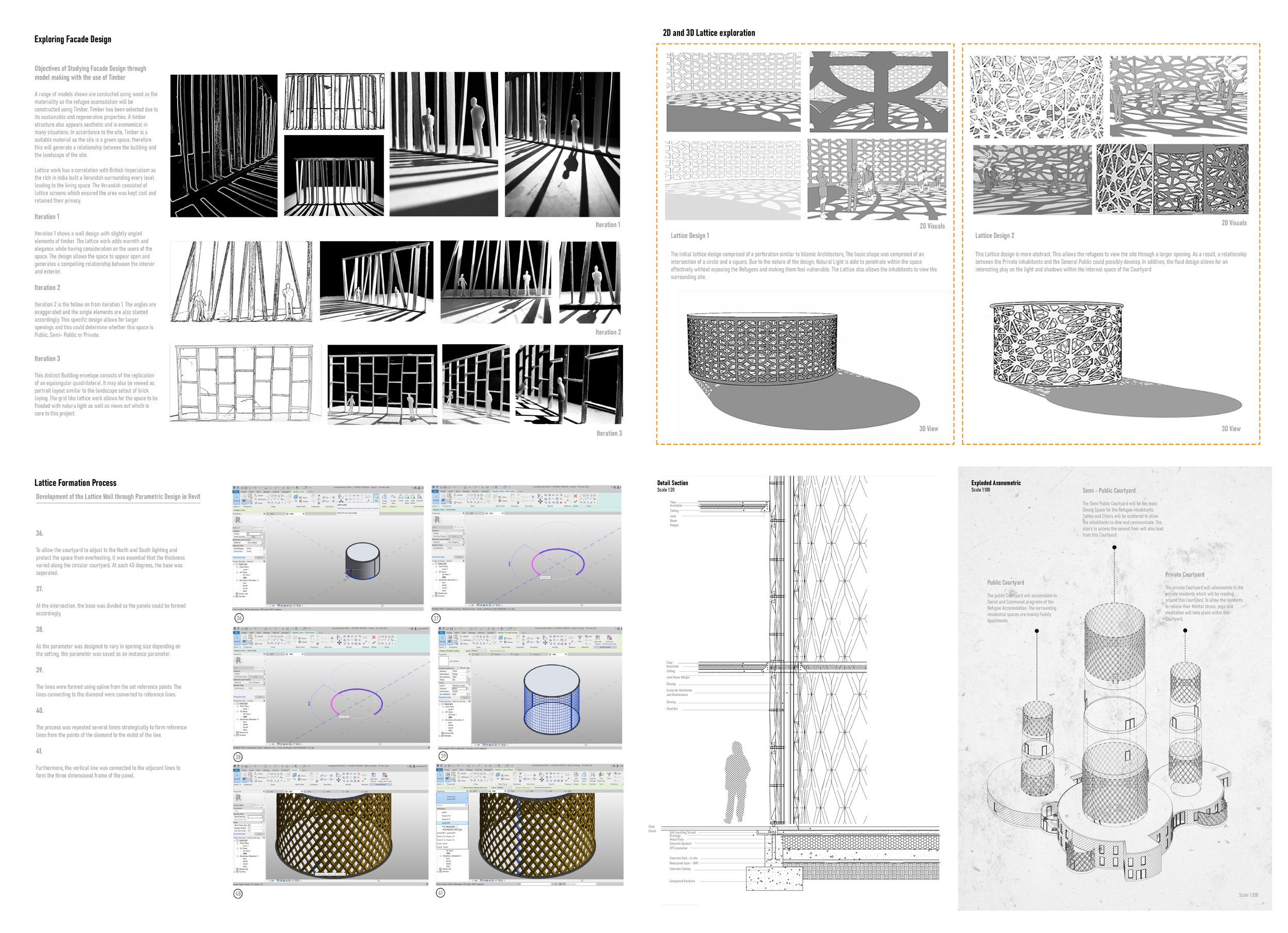

AT3.1 centres on the technological ‘argument’ underpinning the design thesis and forms the strategic proposition for the final building scheme. A critical understanding and knowledge of technology is integrated with the concurrent design studio project.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.2, GC1.3, GC4.3, GC5.1, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.2, GC6.3, GC7.1, GC7.3, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2. GC9.3, GC10.1, GC10.2, GC10.3, GC11.1, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.3, GA1.5, GA1.6

AT3.2

Architectural Technology

The module tests and develops the principles established in AT3.1. Students are expected to examine and articulate the detailed implementation of technological solutions within their concurrent design ‘thesis’ project.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.2, GC1.3, GC4.3, GC5.1, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.2, GC6.3, GC7.1, GC7.3, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2. GC9.3, GC10.1, GC10.2, GC10.3, GC11.1, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.3, GA1.5, GA1.6

Emelie Andrews

Assma Ahmed

Joe Segwick

Linda Gravante

Paige Jones

William Cox

PS1

Professional Studies

Professional studies is a module concerned with issues regarding the Practice of Architecture, particularly those relating to professional context in terms of regulation, organisation and the financial implications of design. The module extends and applies the professional context of the practice of architecture alongside issues explored in the thesis design and technology modules.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.2, GC1.3, GC4.3, GC6.1, GC6.2, GC6.3, GC7.2, GC7.3, GC10.1, GC10.2, GC10.3, GC11.1, GC11.2, GC11.3, GA1.4, GA1.5, GA1.6

Aaron Stanaway - Interdisciplinary Workshop

Cassie Norish - Interdisciplinary Workshop

Charlotte Whittles - Interdisciplinary Workshop

-

Kate Harris - Integrated Design Report

The new government for York is based on a proportional representation voting system, resulting in multiple party rule, with 120 MPs. The Yorkshire Party and York City Council will become the clients for the project, as their ideals are being moulded into the new Parliament building. The focus is to create a Parliament tower to house the assembly room, along with meeting rooms, an education centre and a press centre, to connect the local community with their Parliament and encourage inclusive decision making. The site – the Guildhall – is of significant cultural and historical significance, with consideration to these aspects being important to the development process. With reference to the National Planning Policy Framework, this project aims to sustainably develop the site, and reintroduce the Guildhall to the city.

-

Paige Jones - Integrated Design Report

Set on the banks of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, this project focuses on the invisible barrier between the former refinery site and residents from its surroundings. The Self-Sufficient Reclamation Commune intends to erase this barrier, providing usable spaces in both new and existing architecture for users who have been affected by the refinery, allowing them to reconnect with the site’s potential through a continuous self-building process. Existing refinery towers and infrastructures have been used to store petrochemicals for decades, but they can be cleaned and repurposed to create new, safe and usable spaces for the residents. This will be complemented by creating additional timber modules and platforms using timber and other materials reclaimed from the site, allowing the local citizenry to enjoy transforming the ‘problem filled’ site into a fantastic place to visit, live or pass through whilst remaining sensitive to its rich refinery history.

-

Callum Suttle - Integrated Design Report

The Academy of Anthropogenic Science is an institution that bridges scientific research and community engagement regarding the human impact on the natural environment. Located at the old Philadelphia Energy Solutions Refinery, the project imagines a future where the refinery site has been transformed into an ‘Archaeo-ecological Park’ with the academy as the park’s centrepiece. Here the site has been remediated to its pre-industrial natural habitat. However, the refinery structures - relics of a fossil fuel past – remain to decay, educating future generations of such ecological atrocities. The academy is a central node to an extensive network of elevated walkways. Health and safety requirements have to be central in the planning of this project, focussing especially on pollutant levels, but the mitigation of these becomes a celebrated aspect of the design.

AC3

Context

The module aims to enable the independent identification, definition, description and evaluation or analysis of an appropriate topic, and to acquaint the student with mainstream and alternative architectural languages. The Critical Study allows a degree of student specialisation within their own terms of reference and requires submission of an essay incorporating a critical response to contemporary issues. This is achieved via the reading of relevant literature and lectures by a range of lecturers whose work is related to the design studio themes.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC2.1, GC2.2, GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GC4.1, GC4.2, GC4.3, GC7.1, GA1.4, GA1.6

-

Can "Permitted Development Rights" Address the Housing Shortage in England?

Kevin Dawson

This essay investigates the current Class O of The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order, which allows the conversion of office buildings to dwellings, and examines the process which the Government has followed since the introduction of legislation to deregulate the planning process. The essay also considers the motivation and objectives behind the selection of this specific tool to address the housing shortage in England.

The dissertation argues that, whilst adapting and reusing buildings which no longer fulfil their original purpose can be an effective tool to address the ongoing housing shortage, there should be effective control in place to ensure that the deregulation results in the production of appropriate habitable spaces. These spaces should serve the needs of the future occupier and local people, and create spaces which have architectural quality, are functional, well-proportioned and consider the use of natural light, before considering financial benefits to developers and commercial property owners.

-

Nuclear Power Stations, Biodiversity, and Place

Fin Gilbert

Since the beginning of their use in 1957, nuclear power plants have posed a threat to the immediate and extended environment they are situated in, both through major catastrophes and at a less extreme level through disruption and destruction to the biodiversity of the local environment. This essay looks specifically at Hinkley Point, due to its proximity to a European nature conservation importance - the Severn Estuary – a national nature reserve – Bridgewater Bay – and a Site of Special Scientific Interest - Blue Anchor. This essay uses Hubell’s Neutral Theory to identify shortcomings in current impact assessments, as well as examining case studies including Jarman’s Garden and BIG’s Amarger Bakke to suggest other ways of relating power production and ecosystems, in light of Haraway’s notion of “staying with the trouble” to suggest ways in which power production might have a positive ecological impact.

-

The Portrayal of Social Injustice in the Film “Parasite”

Gabriel Francis Cruz Tallara

The aim of this essay is to see how Bong Joon-ho expresses the underlying issues of social injustice within Parasite (2019) through the languages of cinematography and architecture. The essay uses the theories of Reyner Banham from Theory and Design in The First Machine Age (1960) and David Harvey’s view of what it means to have Rights to The City (2003). Edward Soja’s concept of ‘socio-spatial dialectic’ (2010) links Harvey’s views of the creation of social injustice how these unjust actions affect the geographies of our cities. To understand the meaning of space within architecture, Bruno Zevi (1974) further explains how effective the representation of space within plans and elevations, through architectural drawings. This theoretical structure is then used as a toolkit to analyse the film’s cinematography and architecture, illustrating the material and immaterial realities of social hierarchies in architecture.

-

Industrial Ruin to Public Landscape

Callum Suttle

There is an increasing and global abundance of post-industrial structures left abandoned. These landscapes are left to deteriorate. This essay investigates how shifting aesthetic sensibilities, akin to those of the Romantic era, as well as deliberate placemaking, might re-cast these structures as beneficial elements within our urban space. Placemaking maximises the potential for public space by identifying physical existing assets such as heritage buildings, infrastructure and greenery, each commonly found in post-industrial sites. This essay evaluates current examples, and provides a guide for future architects, covering a range of post-industrial typologies and commenting on their potential to be repurposed as a public landscape. As well as operating at this typological level, the essay applies the various strategies explored in this study to a local example of post-industrial ruin in Leeds. The methodologies are applied with the aim of establishing quality public realm while simultaneously preserving the post-industrial ruin as a new staple of cultural heritage.

-

Why Do Refugee Camps Remain Temporary And What Hinders The Development Of Long-Term Permanence?

Emelie Andrews

This essay looks at “temporary” and “permanent” in relation to refugee camps, initially in physical and structural terms and subsequently through psychosocial aspects. Based on an understanding of works by Manuel Hertz (2013) and Andrew Herscher (2017), it discusses the rationale behind the original production of basic, temporary shelter for refugees and expand on the theories behind why host countries often fail to assure the safety and security afforded by more permanent shelter. From this, the essay moves towards a more psychological understanding of the terms temporary and permanent, discussing how countries have successfully introduced schemes into camps that allow the inhabitants to gain skills through education and work. I will discuss how by providing more than just shelter, refugees are given hope of a more independent, secure future within their destination country and in turn a sense of permanence, not achieved through structure alone, but including examples ranging from trade markets in Kenya to educational schemes in Berlin in order to demonstrate that, by creating opportunities, stability and permanence, refugees can be provided with more than simply a place of waiting and instead have the ability to live fulfilling lives despite displacement. Furthermore, this essay suggests how the need for temporary refugee camps can be reduced, and provides an overview of approaches governments can implement to work towards successful integrational schemes.

Student Video

Level Leader: Claire Hannibal

Tutors: Claire Hannibal, Simon Warren, Tom Vigar, Keith Andrews, Nick Tyson, John Orrell, Carla Molinari, Doreen Bernath, Alia Fadel, Mohamad Hafeda, Will McMahon, Craig Stott, Mohammad Taleghani.

Collaborations: Mike Russum (Birds Portchmouth Russum), Dr Teresa Stoppani (AA), Amin Taha (Groupwork), Ann Stewart (NYCC), Yun Wing Ng (Bauman Lyons Architects) Portsmouth University MArch students, Martin Andrews (Portsmouth University), Phevos Kallitsis (Portsmouth University), Kate Wingert-Playdon (Temple University), Des Fagan (Lancaster University) Jade Moore (alumna), Michele Prendini (alumnus), Graham Davey (alumnus), Hanzla Asghar (alumnus), Joe Earley (alumnus)

BA (Hons) Architecture

Year 2

DC2

Design Communication

The module develops skills in two and three-dimensional techniques including specific Computer-Aided Design packages associated with industry. In doing so students will critically engage with visualisation, communication and design development techniques in their concurrent AD2.1 design module using a variety of graphic and technical means.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.4, GA1.6

Zoe West

Lauren Lee

Joe Downing

Chania Coombs

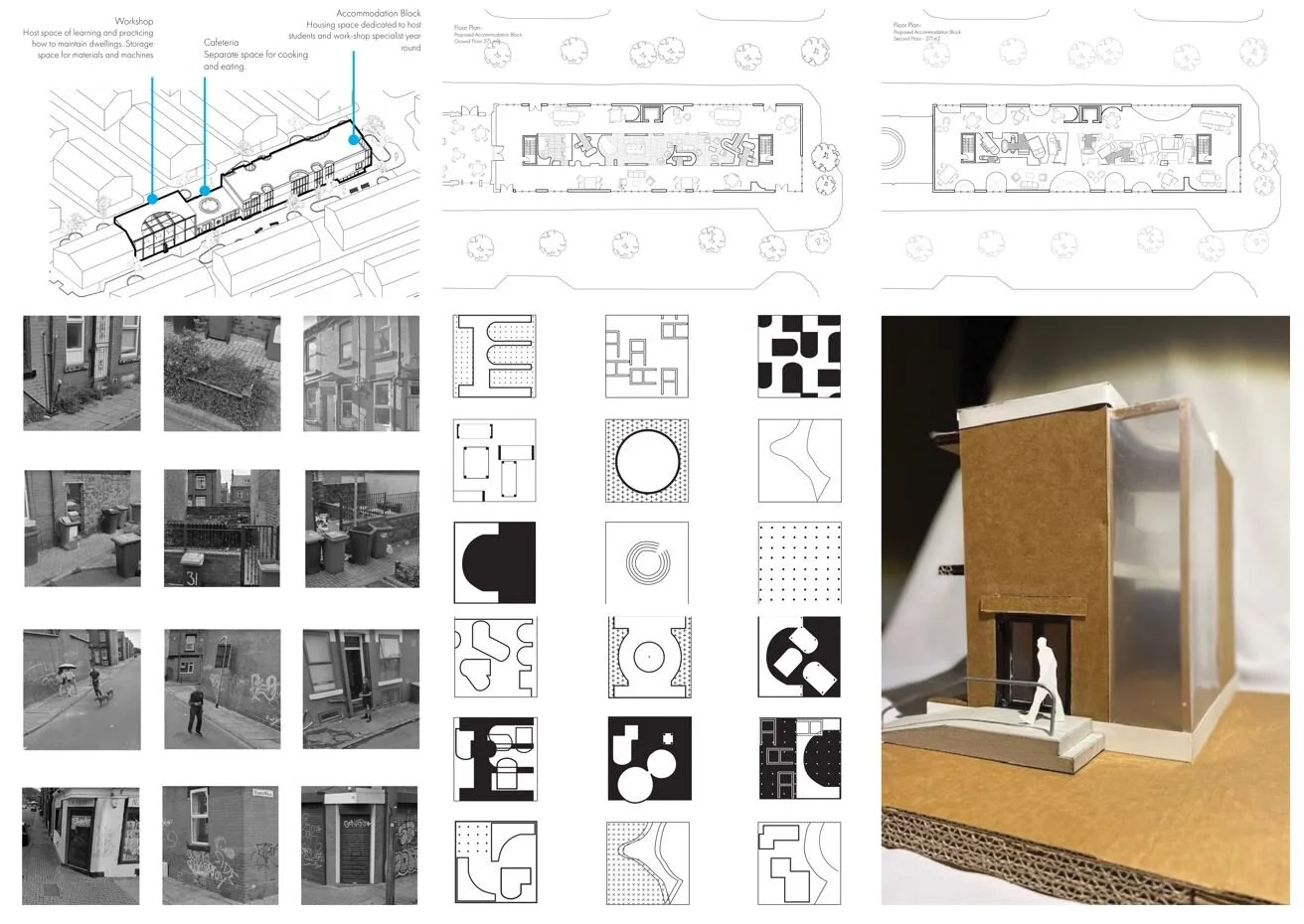

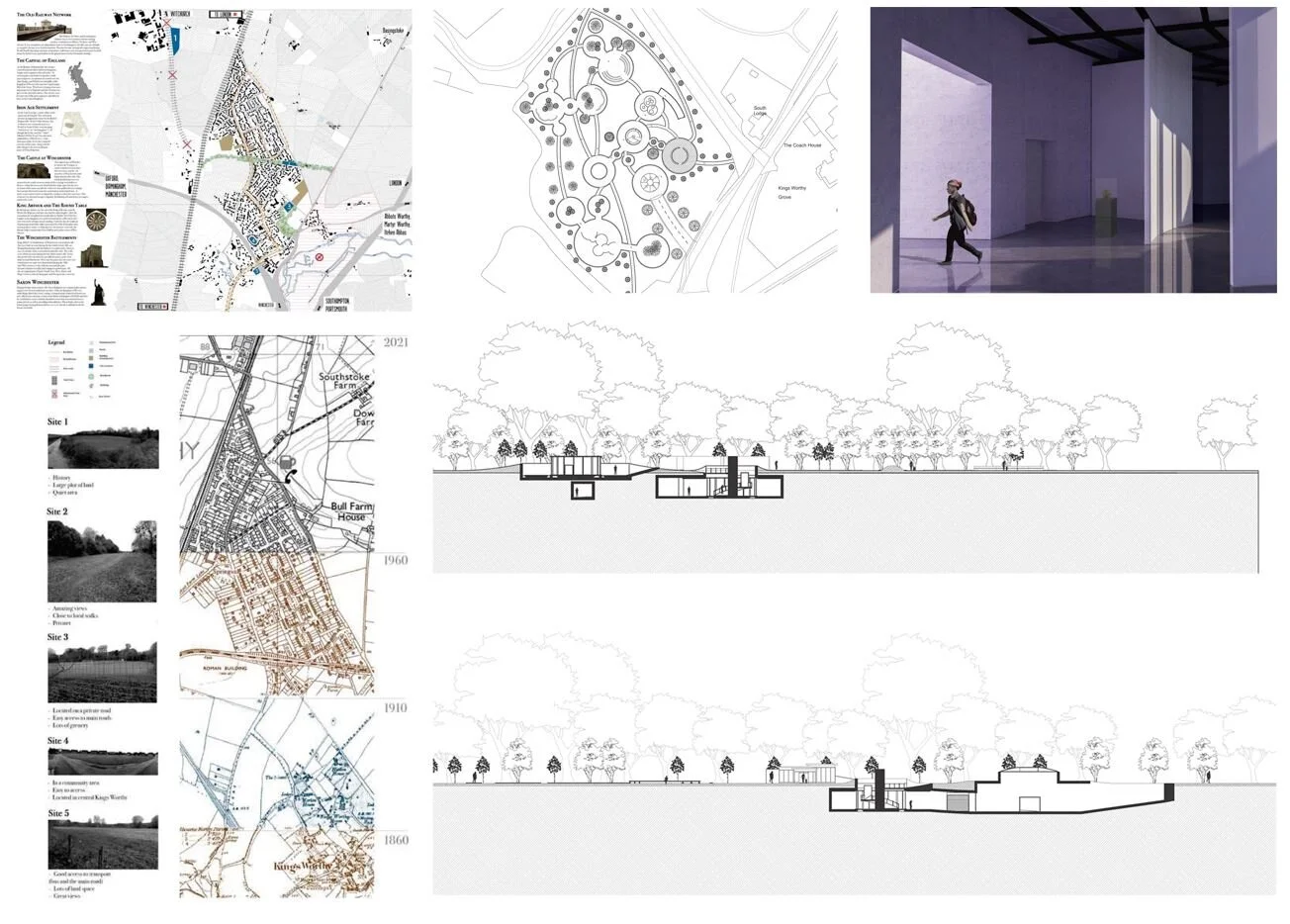

AD2.1

Architectural Design

The first studio module in level 5 aims to develop an iterative approach to design where the design process is used to interrogate problems, with a specific focus upon issues of materiality in design resolution. Students are required to become more critical of methods addressed in level 4 and are encouraged to learn how to question how environment and technology influence the way we design, and vitally the way we should build with materials.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.1, GC1.3, GC2.1, GC2.2, GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GC4.1, GC4.2, GC5.1, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.1, GC6.3, GC7.1, GC7.2, GC7.3, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.3, GA1.4, GA1.6

Emily King

Frazer Wright

Michael Griffiths

Alicea Kenyon

Frazer Wright

Alicea Kenyon

Joe Downing

Katherine Payne

Muhammad Malik

Louis Goss

Zoe West

Jake Lord

Natalia Mata

Rebecca Hurford

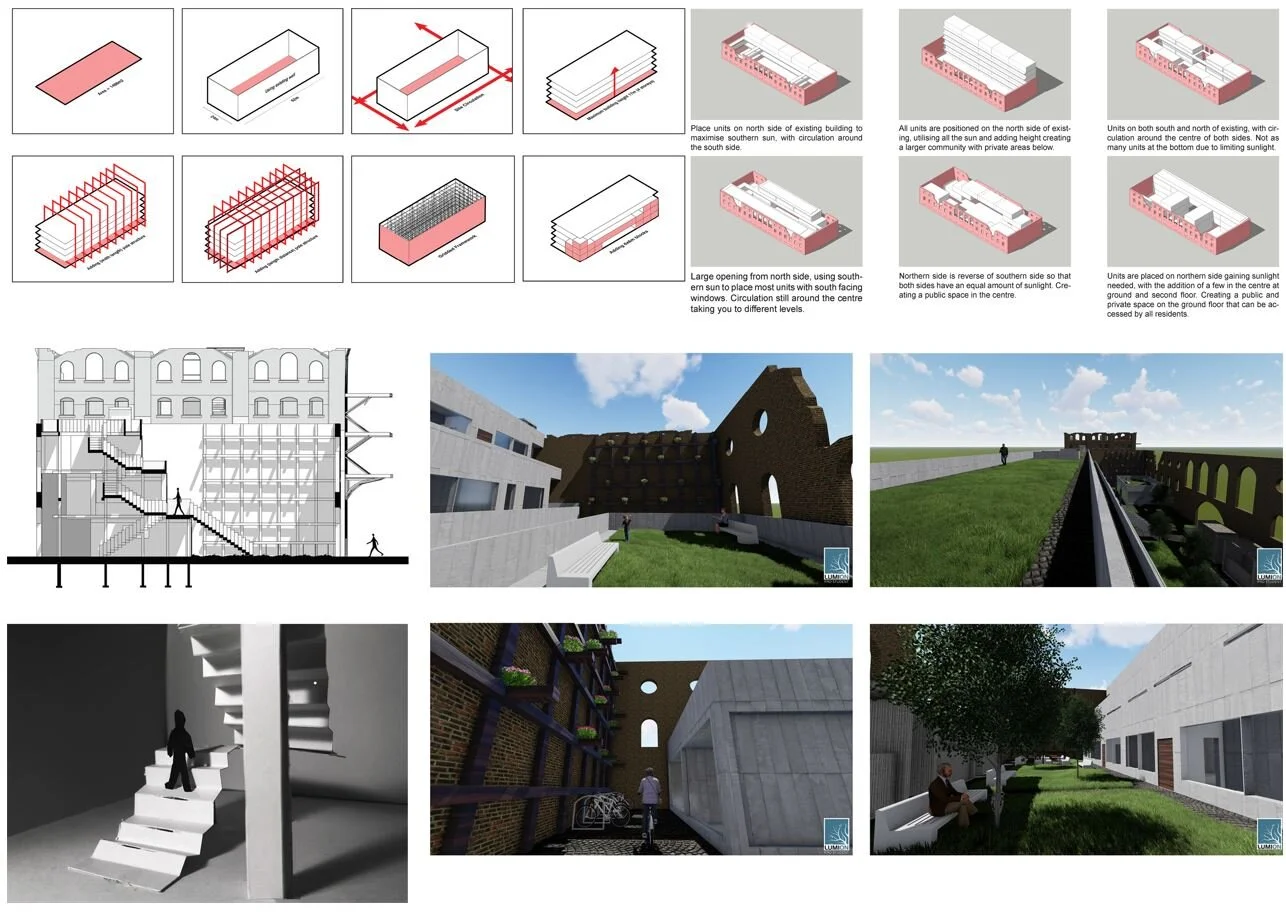

AD2.2

Architectural Design

The second studio design module in level 5 aims to explore more propositional ideas of form-making and representation. The range of tutor groups led by research-orientated staff ensures that an open, active and critical debate is sustained by what constitutes architecture as an exploratory subject, helping foster independent enquiry into experimentation with form-making.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.1, GC1.2, GC1.3, GC2.1, GC2.2, GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GC4.1, GC4.2, GC4.3, GC5.1, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.1, GC6.2, GC6.3, GC7.1, GC7.2, GC7.3, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2, GC9.3, GC10.1, GC10.2, GC10.3, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.3, GA1.4, GA1.5, GA1.6

Frazer Wright

Jake Shipp

Nicole Oliver

Nicole Oliver

Nicole Oliver

Chi Hong Tai

Lauren Lee

Patrick Roobotom

Louis Gross

Curtis Black

Louis Gross

Victor Magalhees

Joe Downing

James Higgins

Jake Lord

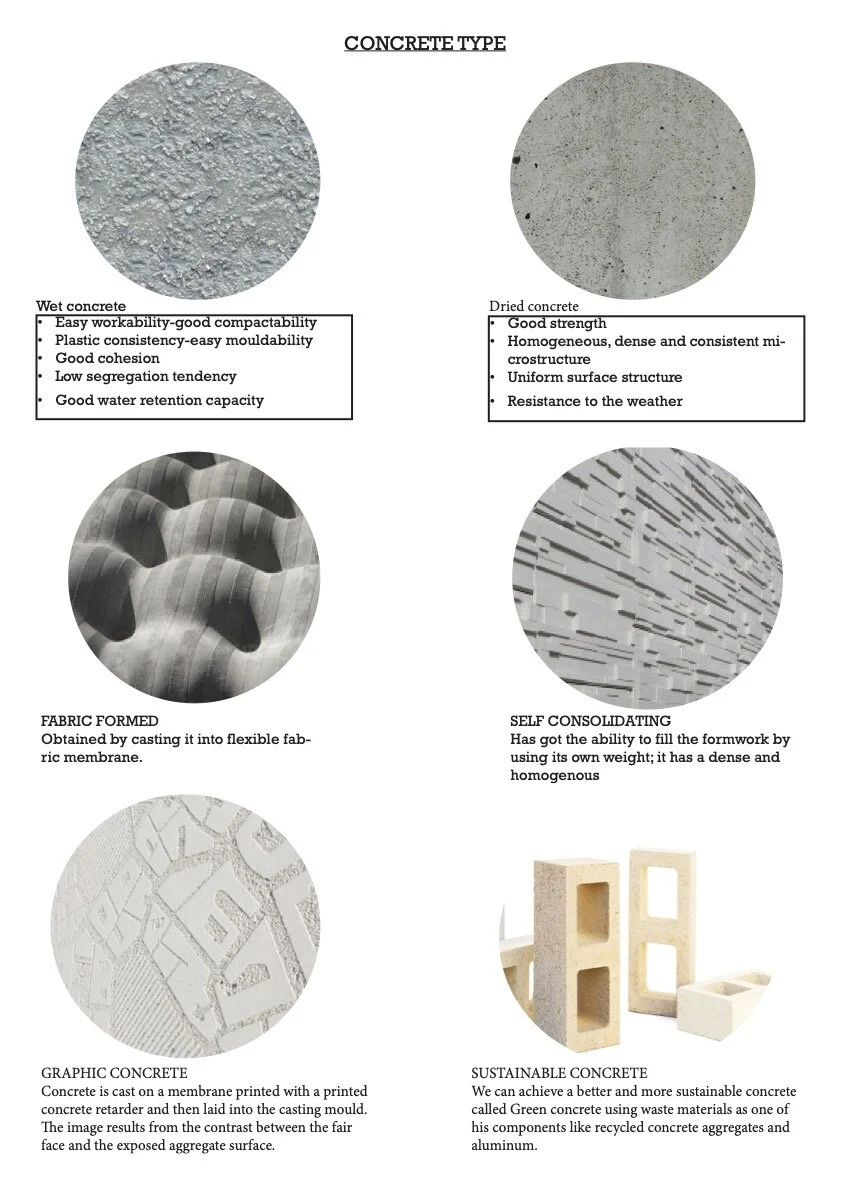

AT2.1

Architectural Technology

Building on the level four experiential base, AT2.1 focuses on developing an understanding of strategies within existing buildings in order to develop a toolkit of technological approaches that can be used within students’ design work in the concurrent AD2.1 design studio.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.2, GC1.3, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.2, GC7.1, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2, GC9.3, GC10.1, GC11.1, GA1.3, GA1.6

Phetnarin Chumsook

Reece Harrison

Curtis Black

Joe Downing

Roukan Moustafa

Nicole Oliver

AT2.2

Architectural Technology

The AT2.2 module requires students to demonstrate a clear understanding of the integrated technological principles that have been used to inform their AD2.2 design studio project.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.2, GC1.3, GC5.1, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.2, GC7.1, GC7.3, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2, GC9.3, GC10.1, GC10.2, GC10.3, GC11.1, GA1.3, GA1.6

Joe Downing

Louis Gross

Patrick Roobottom

Rebecca Hurford

Louis Gross

Patrick Roobottom

AC2.1

Context

The module explores the history of cities in their multiple states of development and expands on issues raised in AC1.2, offering insights into real situations which cities have to face - competitions, threats, disasters, wars, expansions, divisions, migrations, dilemmas, controversies and demises. The analysis of the history of the City and site, urban context, and a reading of the evolution of communities identified in the AD2.1 design module encourages students to read, research and write analytically as well as develop their graphical and verbal representations.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC2.1, GC2.2, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC4.1, GC4.2, GC4.3, GC7.1, GA1.4

-

How Has Surrealism Shaped Contemporary Architecture

Shannon O’Donnell

In ‘The Manifesto of Surrealism’ Andre Breton claims that “Reality[…]continues to exist in the state of a dream” leading us to question if this statement holds vice versa. Perhaps dream-like qualities pursue an existence in reality using surrealism by incorporating it into contemporary architecture. Many users find that reality lacks opportunity to ‘escape’ from the pressures of everyday life, and this essay postulates that there is a thread of architecture that might be called surrealist which works to move into this dreamlike escape. This lineage is traced from Ledoux, whose attention was caught by the desire to exert the creative possibilities of the human subconscious in physical works. From there, the essay looks at Cheval’s Palais Ideal, and Edward James’ Los Pozas Sculpture park, which are both visions of difference, existing somewhere between reverie and actuality, before arguing that recent increases in stress levels have led to an increased need for such surreal architectures, and that therefore works of contemporary architecture like the transparent church by Van Vaerenbergh and Gijs can be read as being part of the surreal tradition.

-

Heaven Without Hell

Timothy West

Utopia, the concept and idea came from Thomas More who, in 1516, wrote about an island that he named Utopia. The word itself comes from Greek, translating to “no-place”. More had a strong Christian background – he has been canonized, and strongly contemplated becoming a monk. Utopia’s original plans can be compared to life within the monastery walls, which was strictly regimented. The Bible describes how difficult it will be to make it to Heaven, and that the majority will fail, resulting in eternal destruction in Hell. This essay asks, was Hell purposefully built, or was it a result of the poor planning of Heaven? What becomes apparent when looking at examples of utopic projects, however, is that they generally respond to a problematic current situation – be it the “dark satanic mills” or religious persecution. This essay therefore concludes that Dystopia or Dystopic environments are the main catalyst or cause for the idea of Utopia. The strong religious foundations of the word make the two inseparable. There can be no Heaven without Hell, or Utopia without Dystopia, the concepts would not exist or survive without the other.

-

Can Commoning be Sustained During Increasing Economic and Cultural Globalisation?

Zoe West

The progression of transnational economic and cultural networks, mostly due to new means of transportation and communication systems, generates a homogenous culture, whilst neglecting local cultures and their natural surroundings. Commoning counteracts the indifference of globalism by refocussing on the community’s immediate surroundings and citizens, by mutual aid, and the devaluation of enclosures. Commoning projects like the Bologna Regulation of 2014 have been able to reduce the antagonism provoked by the ‘neoliberal privatisation and commodification … carried out through the complicity of the State with the Market’ (Bianchi, 2018, p.289), illustrating that commoning can be sustained and even supported by growing cultural globalisation, especially in light of contemporary digital technology. Projects like R-Urban, however, illustrate that communing in this manner will be shut down and even erased once they threaten to hinder the progress of neo-liberal globalism. However, Nepal’s community forestry projects can be seen as both a result of, and a countermeasure to, increasing globalism. It is clear that commoning can function within our increasingly globalized society, but most current examples are relatively small, and are not viewed as threats to globalization. However, if these schemes were to grow, then it is probable that neoliberal power would to intervene.

AC2.2

Context

The module reinforces the understanding of concepts raised in AC2.1 in relation to the city, and introduces specific theoretical issues related to urban context, urban planning, community and the City. The module focuses upon a number of urban sites in support of the concurrent AD2.2 module briefs to provide the student with an underpinning to design studio work in relation to urban context.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC2.1, GC2.2, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC4.1, GC4.2, GC4.3, GC7.1, GC7.3, GA1.4

-

Immigration Detention Architecture as a Catalyst for Spatial Resistance

Emilie King

This essay explores some of the ways immigrants have suffered through the process of passing through immigration detention centres - the holding of immigrant populations against their will by governments of host nations. This process can happen at the border when a person or group of people are detained immediately or when they have lived within our community for years and attempt to renew their visa (DetentionAction, 2020) - how spatial struggle can and has led to immigrant spatial resistance; how immigrants are seeking spatial justice and how they are taking back their spatial right through three key topics: control, resistance and justice. Focusing on detention/incarceration centres in Toronto and Illinois, this essay highlights the criminalisation of immigrants through spatial control, how these centres affect families, and how architecture is integral to this process, both in terms of the designed control mechanisms put in place by architects, and in the ad hoc modifications those incarcerated use to retake control of their surroundings.

-

The Role of Visual Semiotics in Shaping Collective Tactics for Spaces of Resistance

Zoe West

I was met with a disarray of footprints in the snow, each leaving a unique impression. The snow created another layer of information normally concealed from us – it uncovered a new spatial narrative about the rhythm of movement in this space and the way people manoeuvre through it. Spaces are organised and boundaries are exposed, revealing social, economic and cultural divides, through the direction, displacement and concentration of footsteps in particular areas. The compounding of footsteps made it difficult to discern a single footprint journey and therefore practically impossible to follow, and so I decided to navigate this environment based upon my subconscious impulsive decisions. The blanket of snow obscured the boundaries of public spaces.

Our perception of spaces is conditional; respective of geographical, social, economic, cultural and emotional circumstances, as well as our practical uses of the physical environment; partly shaped by the changes in the ‘representations of space’ (Jaworski & Thurlow, 2010, p. 4). It was evident that these subconscious impulse decisions for the route were not truly random, but were influenced by the personal familiarity; memories, perceptions and preconceptions, as well as external influences. Everyone who traversed the space constructed a different spatial narrative that reflected themself as an individual, and traces of these modes of behaviour left on the landscape can influence those who come after. It was through the perceiving of the agglomeration of footstep trajectories that a collective participation could be interpreted. These can be seen as a collective tactic that becomes a space of resistance against conventionally defined spaces.

-

How has the Gentrification of Ancoats Impacted the Community’s Right to the City?

Alicea Kenyon

Gentrification is the “process by which poor and working-class neighbourhoods […] are refurbished via an influx of private capital and middle-class homebuyers” [Smith, 1996]. These neighbourhoods are often inner-city communities that have experienced disinvestment. The gentrification of Ancoats was made possible initially by the demolition of the Ancoats Dispensary - this was a direct attack on the social reproduction of this working-class community. Although deemed an effect of gentrification, was clearly a “prime strategy towards urban economic restructuring” [Luke & Kaika, 2019). The Dispensary served as both spatial infrastructure that supported the community’s social reproduction, and a symbol of the community’s existence and continuity throughout history. Gentrification is a class issue. It poses a class remodel of the city’s landscape. Ancoats was home to those who worked in the mills and factories, the backbone of the Industrial Revolution. The relationship with the historical infrastructure of the area stems from the working-class identity assumed by those “in the face of deindustrialisation and generational unemployment” [Luke & Kaika, 2019] and it becomes clear as to why these historical buildings – such as the Ancoats Dispensary – embody social reproduction and resist gentrification, with their demolition only further enabling spatial injustice of a community.

Student Videos

Level Leaders: Craig Stott and Anna Pepe

Tutors: Craig Stott, Anna Pepe, Ian Fletcher, Olivia Neves Marra, Mohamad Hafeda, Jose Navarette, Jake Parkin, Michelle Martin, Keith Andrews, Claire Hannibal, Sarah Mills.

Collaborations and links have been developed with: Rozita Rahman (Circle Studio), Alex Vafeiadis (Atkins), Philip Watson (HLM Architects and Leeds University), Roberto Boettger (AA), Susan Bone, Alvaro Velasco Perez (AA), Kara de los Reyes (University of West England and AWW), Gabriela Dalhoeven Telleri (Vital Architecture), Ye Jin Lee (AAction), Julio Torres Santana (Wentworth Institute of Technology), Tyen Masten (PHASE3 and AA), Jimenez Lai (UCLA, AA and Bureau Spectacular), Jeffrey Liu (Princeton and Yale), John Ng (AA and RCA), and Ashley Ball (Leeds Beckett and Store and Archive).

BA(Hons) Architecture

Year 1

DC1

Design Communication

The module facilitates the skills necessary for the detailed exploration and communication of architectural design ideas. Incorporating analytical and formal architectural drawing and essential two and three-dimensional skills it develops a critical understanding of specialist visualisation, modelling and technical approaches to design.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.4

Aidan Salari

Benson Logan

Bethany Hall

Elsa Whittaker

Joseph Oates

Matthew Coyne

Stavri Kozakou

Ahd Hussain

James Robertson

AD1.1

Architectural Design

AD1.1 incorporates the learning of foundational subjects inherent to the discipline of architecture together with useful skills and habits of good studentship. The focus for the student is to acquire theoretical and practical knowledge that help to relate design, theory and discourse. Skills of analysis, design and representation are developed via a number of techniques using a wide range of media.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC2.1, GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.4

Hussain Owais

Georgia Clayton

James Robertson

Joseph Oates

Niamh Ashley

Elisabetta Angius

Stavri Kozakou

Elisabetta Angius

Elisabetta Angius

AD1.2

Architectural Design

The module introduces the architectural design of more complex spaces, including buildings. It reinforces and integrates developmental work undertaken in AD1.1 relating to creative solutions to design briefs, and integrates the knowledge of technology, environment and construction undertaken in the concurrent AT1.2 Technology module.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.1, GC1.3, GC2.1, GC2.2, GC2.3, GC3.1, GC3.2, GC3.3, GC4.1, GC4.2, GC5.1, GC5.2, GC5.3, GC6.3, GC7.1, GC7.2, GA1.1, GA1.2, GA1.4

Elisabetta Angius

Elsa Whittaker

Elisabetta Angius

James Robertson

James Robertson

Matthew Coyne

Matthew Coyne

Niamh Ashley

Niamh Ashley

Owais Hussain

Owais Hussain

AT1.1

Architectural Technology

This introductory module in Technology engages the students with the key principles of sustainability, structure, construction and environmental science in order to understand the fundamental elements of building.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.3, GC5.2, GC7.1, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2, GC9.3, GA1.3

AT1.2

Architectural Technology

This module in Technology develops students’ understanding of sustainability, structure, construction and environmental science, via a hands-on approach to realizing fundamental building principles. Creative opportunities inherent within the production of buildings are explored and linked with AD1.2.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC1.3, GC5.2, GC7.1, GC8.1, GC8.2, GC8.3, GC9.1, GC9.2, GC9.3, GA1.3

AC1.1

Context

Movements in art have predicated and influenced architectural design – AC1.1 aims to investigate this connection through the analysis of key issues that have characterised and influenced architectural design. The module fosters the development of the ability to use written and graphical means to define various approaches to the representation of architectural space. The content aligns with the concurrent DC1 and AD1.1 – both studio-based modules that aim to develop methods of communication and architectural representation through varied mediums.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC2.1, GC2.2, GC3.1, GC3.2, GA1.4

-

The Experience of Architecture through Cinema and Models

Elisabetta Angius

The relationship between architecture, models and cinema finds its roots deep into the history of humanity, and since then they have been a precious tool in the hands of creative minds to empower our knowledge and guar¬antee our collective memory. The proximity of the model with the reality, its capacity to be instantly read from the eye and to be touch thanks to its three-dimensionality distinguishes it from the other media. Most of all, cinema can provide evaluable experiences in changing our conception of space and existence through the exercising and the realization of the imagined, entering at the same time deeply in contact with the human emotions. Cinema makes possible to explore that three-dimensionality using ideas and cameras, bringing it to life in the way people perceive it as spectators and protagonists at the same time. This essay will explore the potentialities of cinema and models in representing the experience of architecture, finally creating a visual experimentation that merges the two media together.

-

Power of Words v Photography: History of architecture, from The Ten Books to Las Vegas

Owais Hussain

Painting a story in architecture is vital in understanding a building and its function, but is also crucial in identifying the architect’s purpose for the building. Two of the most significant media to do this are photography and words. Photography is arguably one of the prime media for architecture, due to the accessibility, convenience, and its ability to communicate and document a building. The obsession with photography has grew simultaneously with the growing technology, from the first photograph by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce to smartphones. Nevertheless, one may argue that words are in fact more pivotal in their effect on architecture, as they refine the architect’s purpose successfully. Words have captured history throughout architecture, from Vitruvius to architects like Denise Scott Brown, who have respectively influenced architecture through the agency of their words. This essay will compare these two media, considering in particular how they have been used by architects to express their intentions and agendas.

-

Exploring the Translation of Information and Experiences within two chosen Methods of Representation

Georgia Clayton

Architecture is not simply the construction of a building, it is an obtuse potential for the mind to flow and create homes, sculptures, movies and imaginative drawings; focusing on the translation of information in order to manufacture the client’s requirements. There are many methods of representation available to demonstrate an architect’s vision or even the actual reality of the experience and purpose of a building, for example through drawings and cinema. The exploration of the advantageous qualities and potential flaws of these media demonstrates the ease and necessity of providing the required information from one another to not only construct a structure or building but additionally, create an atmosphere that allows one to experience it despite not be able to physically move in the proposed space. Analysing these methods allows a greater understanding of both, thus providing the correct information to allow them to be utilised in the way that would benefit and project the corrects aspect of a design that the architect wishes to demonstrate.

AC1.2

Context

The module provides a broad foundation of architectural histories and theories including key architectural movements and architects in order to provide a framework to analyse, evaluate, observe, speculate and anticipate how such developments have catalysed design. The module consolidates the information covered in AC1.1 and is used to support developing design proposals in the concurrent AD1.2 studio design module.

PSRB criteria mapping: GC2.1, GC2.2, GC3.1, GC3.2, GA1.4

-

How Was Architecture Used to Portray Power in Nazi Germany?

Ruth Amissah

This essay explores some of the most important structures of the Nazi Party and aims to understand the features that they were designed with to create an impression of power, authority and superiority. This is seen against a background of the collapse of the German economy post-WW1, and the use Hitler made of this to garner support. Hitler wanted to design buildings at a scale that had not been achieved before: “I need grand halls and salons which will make an impression on people, especially on the smaller dignitaries… The cost is im-material.” (Speer, 1970). This essay also notes Ishida’s “ruin theory”, and sees the monumentality and lack of ornamentation in Nazi architecture as aiming to communicate the great history of potency delivered by the dominions (Ishida, 2018). The essay also discusses the Cathedral of Light, which in 1936 used some 130 anti-aircraft searchlights as part of its architectural theatrics. Hitler commented that the use of searchlights would make other counties think that they were “swimming in searchlights” (Speer, 1970, p. 101). In other words, this essay covers the use of architecture as a communicative tool to the German people, to contemporary powers, and to future generations.

-

How Immateriality Leads to a More Functional Disposition of the Material Spaces in Architecture

Elisabetta Angius

Architecture is generally identified with a fixed entity – the building, and its materiality. This essay looks instead at the ephemeral aspects of architecture, those things concerned with the absence of matter (immateriality), which can be read as the sum of sensorial experiences such as taste, touch, smell and so on (Pallasmaa 1996; Karandinou 2011). This would be a truly functional architecture – one that works on its users. In the era of Modern architecture, with walls substituted for transparent glazed surfaces, and with no separation between the domestic spaces or even sometimes the interior and exterior, we were already dealing with immaterial architecture that could be perceived as one single immutable space, instead of a dynamic sequence of spaces. This became especially true in the work of Hadid, where she shows a floating architecture, where the ambiguity of the plans is shown as a constellation of possibilities that flows in many different directions (Foster, 2006) that uses the material only as a means to generate an immaterial, functional experience.

-

How WW2 Impacted Social Housing in Europe in the 20th Century

Owais Hussain

“The essential act of war is destruction, not necessarily of human lives, but of the products of human labour” (Orwell, 1949). Physical safety is clearly crucial to architecture, but WW2 left many houses destroyed, and after the war, people needed a sense of hope and an optimistic future, as destruction, ruin and unemployment and housing shortages were widespread. However, Balfour suggests, perhaps this “horror and degradation of its destruction represented a necessary catharsis, necessary to erase the past and make way for the modern world. The war had been an act of liberation.” (1990). As hope was restored, it was strengthened by the introduction and use of “New Brutalism”, which valued functionality, honesty of structure and materiality and a sense of overall simplicity, which was used in social housing to connect disadvantaged communities to the building. They were the calculations on a clean sheet of paper Le Corbusier had suggested. However, it became apparent that this all betrayed an ignorance to the true scale of problems affecting society, in turn making social housing itself seem like a work of ignorance. The war had allowed communities and architects to forget their past, for better and for worse.

Student Experience Videos

Hear below from BA1 students Elisabetta, Ruth and James.

Level Leader: Carla Molinari

Tutors: Carla Molinari, Ashley Caruso, Jo Lintonbon, Mohamad Hafeda, Will McMahon, Sarah Mills, Anna Pepe, Michelle Martin, Craig Stott, Simon Warren, Keith Andrews, Ian Fletcher.

Partners: Collaborations and links have been developed with: East Street Arts Leeds, Nicolas Henninger, Nikola Yanev (Caroe Architecture Ltd.), William Gains (Bowman Riley), Marco Spada (University of Suffolk), MArch students (Leeds School of Architecture)

BA(Hons) Architecture

RIBA Part 1

This course takes students through the key principles of architecture, led by design but strongly and integrally supported by both technology and context modules, as well as introducing them to the standards and practices that are expected of them within the profession.